Why Change Management Is a Patient-Safety Imperative in Healthcare

By Luisa Santos,.

August 28, 2025

Healthcare organizations don’t fail at change because the plan is wrong—they fail when people aren’t ready, safe, or motivated to work in the new way. Organizational readiness for change is a shared psychological state—people’s collective commitment to the change and their confidence they can deliver it. When readiness is high, teams initiate change faster, persist when it’s hard, and collaborate more effectively; when it’s low, even well-funded initiatives stall.

Readiness is necessary but not sufficient. Healthcare changes succeed when we manage the context around the work: leadership support, workflow fit, resources, and measurement. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) distills these factors into five domains—intervention characteristics, outer setting, inner setting, characteristics of individuals, and process—so leaders can identify barriers and design targeted strategies rather than push generic rollouts.

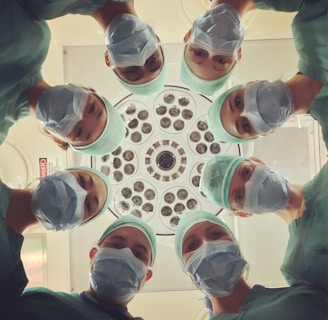

The human core of safe care is psychological safety—a climate where clinicians can speak up about errors, near misses, and process risks without fear of embarrassment or punishment. Amy Edmondson’s research shows psychologically safe teams learn faster and perform better, which directly supports incident prevention, handoff quality, and escalation culture. Building safety requires visible leader behaviors (inviting input, responding appreciatively), structured learning routines (huddles, debriefs), and peer norms that reduce status barriers.

Motivation matters as much as method. Self-Determination Theory shows people adopt and sustain new behaviors when three needs are met: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. For healthcare change, that translates into co-designing workflows with frontline staff (autonomy), role-based practice and simulation (competence), and strong interprofessional communities of practice (relatedness). These conditions turn compliance into commitment.

Finally, behavior change must be designed, not assumed. The Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) links what we want people to do with the actual levers that shape behavior—Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation (the COM-B model)—and a set of intervention types (e.g., training, environmental restructuring, incentives). In a medication-reconciliation initiative, for example, BCW prompts us to pair EHR workflow tweaks (Opportunity) with brief coaching and checklists (Capability) and peer recognition for reliability (Motivation).

What great looks like in healthcare change

Leadership: sponsor rounding that asks, “What’s getting in the way?”—and removes it.

Safety psychology: daily huddles + after-action reviews with blame-free language.

Motivation: co-create metrics that matter to clinicians (e.g., fewer re-work loops, safer handoffs).

Behavior design: make the right action the easy action (defaults, checklists, visual cues).

Readiness & context: use CFIR to map barriers and assign owners early.

Bottom line: Patient outcomes improve when people are ready, safe to speak up, and intrinsically motivated—and when leaders shape the context to support the new way of working.

Resources

Damschroder, L. J., Aron, D. C., Keith, R. E., Kirsh, S. R., Alexander, J. A., & Lowery, J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(50). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50.

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999.

Michie, S., van Stralen, M. M., & West, R. (2011). The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science, 6, 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-42.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://selfdeterminationtheory.org/SDT/documents/2000_RyanDeci_SDT.pdf.

Weiner, B. J. (2009). A theory of organizational readiness for change. Implementation Science, 4(67). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-67.

Making Technology Change Stick in IT: A People-First Playbook

By Luisa Santos,.

July 16, 2024

IT transformations fail for human—not technical—reasons. We ask teams to adopt new platforms, pipelines, and controls without preparing their motivation, capability, and context to change. Decades of research in information systems shows adoption rises when users believe a system is useful and easy to use—the core of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). Translating TAM into practice means designing with users, simplifying workflows, and removing friction so benefits are felt immediately

Culture is the multiplier. Large-scale studies of high-performing software organizations find that psychological safety, lightweight change approvals, and continuous learning correlate with faster delivery and better stability—more deployments, shorter lead times, and lower change-failure rates. These outcomes aren’t accidents; they emerge when leaders reduce fear, invite experimentation, and measure flow rather than heroics.

Yet leaders still repeat the classic mistakes: under-communicating vision, declaring victory too early, and failing to anchor new behaviours in culture. John Kotter’s work on transformation highlights these traps and the leadership moves that avoid them—building a guiding coalition, creating short-term wins, and hardwiring new habits. Pairing that with Prosci-style adoption planning (Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability, Reinforcement) gives teams both the story and the scaffolding for change.

Sustained adoption also depends on motivation. Self-Determination Theory reminds us that people stick with change when they feel autonomy, competence, and relatedness. In IT, that means giving teams input into tooling choices (autonomy), hands-on enablement and pairing (competence), and communities of practice or guilds (relatedness). These conditions turn “mandates” into momentum.

Finally, treat behavior change like a product. The Behaviour Change Wheel/COM-B prompts us to identify the exact behaviors that drive outcomes (e.g., trunk-based development, test automation, incident reviews) and then choose interventions that increase Capability (skills, job aids), Opportunity (tooling, environment), and Motivation (feedback, recognition). This closes the gap between “new process” and new habits.

A practical roadmap for IT leaders

Co-design for usefulness (TAM): reduce steps, surface wins in the UI, measure adoption.

Lead for safety and speed: blameless postmortems, small batch sizes, automated tests; track deployment frequency, lead time, MTTR, and change-failure rate.

Anchor the narrative (Kotter): clear vision, visible coalition, short-term wins every 4–6 weeks.

Design the behaviors (BCW/COM-B): training + pairing (Capability), ergonomic tooling (Opportunity), social proof & recognition (Motivation).

Reinforce: dashboards that show team progress, manager one-on-ones focused on learning over blame.

Bottom line: In IT, the fastest path to better delivery isn’t a new tool—it’s leading people through change with clarity, safety, and behaviour design.

Resources

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. https://www.jstor.org/stable/249008.

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999.

Forsgren, N., Humble, J., & Kim, G. (2018). Accelerate: The science of lean software and DevOps—Building and scaling high performing technology organizations. IT Revolution Press. https://itrevolution.com/product/accelerate/

Kotter, J. P. (1995). Leading change: Why transformation efforts fail. Harvard Business Review, 73(2), 59–67. https://hbr.org/1995/05/leading-change-why-transformation-efforts-fail-2 (open PDF reprints available).

Michie, S., van Stralen, M. M., & West, R. (2011). The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science, 6, 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-42.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://selfdeterminationtheory.org/SDT/documents/2000_RyanDeci_SDT.pdf.

Connect

Get in touch with our consulting team.

Explore

+1 437-604-1388

© 2025. All rights reserved.